No, James Safechuck Didn’t Lie About the Thriller Jacket—Here’s the Full Story

April 20, 2020

In the documentary Leaving Neverland, James Safechuck recounts a vivid memory from his early years of spending time at Michael Jackson’s Hayvenhurst estate. As he tells it, during one visit, Jackson led him into a closet filled with stage costumes and personal items, inviting him to pick anything he liked. Naturally, James chose the most iconic item in sight: the Thriller jacket. “Go big!” he quips in the film, reflecting on the moment with childlike enthusiasm. He even remembers wearing the jacket out to the local supermarket, such was the thrill of owning a piece of pop culture history.

We went into the closet [at Hayvenhurst] and we were looking at his stuff, and he told me I could pick out a jacket. I could have that; it would be mine. I picked the Thriller jacket, of course. Go big! And I took it home. I wore it to the grocery store.

However, some corners of the internet have since seized on this anecdote in an effort to undermine James's credibility. According to Julien’s Auctions, there are two known Thriller jackets associated with Jackson—one of which fetched $1.8 million at auction in June 2011, purchased by the Verret family from Austin, Texas. The second is reportedly housed in a museum collection.

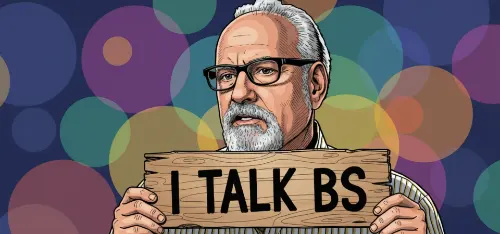

A Twitter account called “Leaving Neverland Facts,” widely believed to be affiliated with Jackson’s estate or at least its defenders, published a post highlighting the apparent inconsistency. The tweet reads:

Hmm.. one of 2??? In #Leaving Neverland James Safechuck says at a visit to Michael's Hayvenhurst home he was told to pick from a closet anything he wanted "I picked the Thriller jacket, of course--go big--and I took it home." So did he sell it? Is the story even true?

The implication is clear: either James secretly sold the jacket for profit or, more provocatively, fabricated the story altogether.

But this line of questioning fails under closer scrutiny. Crucially, James Safechuck himself clarified the situation years earlier in a formal civil complaint submitted during legal proceedings. In that document, he explains that Jackson allowed him to handle and try on a variety of jackets, including the Captain EO outfit. Jackson then gifted him the Thriller jacket outright. However, a few years later, Jackson requested the jacket's return, assuring James that it would be displayed in a museum on his behalf. Jackson even promised that a plaque would accompany the display, reading “On loan from Jimmy Safechuck.” To soften the blow, Jackson allowed him to choose between two alternative jackets featured in the Thriller music video—one from the "Zombie" scenes, and the other a pristine version—to keep instead.

DECEDENT let Plaintiff touch and play with his many jackets. DECEDENT let Plaintiff try on the 'Captain EO' jacket, and gave him the Thriller jacket to keep. DECEDENT took back the Thriller jacket a few years later, saying that the jacket would still belong to the Plaintiff, but that he needed to display it at a museum. The DECEDENT told Plaintiff that there would be a plaque saying 'on loan from Jimmy Safechuck.' In the meantime, the DECEDENT let Plaintiff choose between two of the other jackets used in the Thriller video—the 'Zombie' jacket and the 'clean' one.

So why wasn’t this additional context included in the Leaving Neverland documentary? The answer lies in the nature of documentary filmmaking. Documentaries are not exhaustive autobiographies; they are carefully edited narratives designed to convey core themes and emotional truths. Filmmakers often face difficult decisions about which details to include and which to omit for the sake of narrative pacing and impact. Exploring the administrative logistics of returning a jacket could easily be seen as extraneous when weighed against the broader, more serious issues the documentary sought to expose.

Furthermore, there is a broader pattern at play here. Michael Jackson had a well-documented history of giving personal items—often clothing—to the children and young people he befriended. A famous example is the fedora worn in his Smooth Criminal performance, which he gifted to Wade Robson, another figure featured in the documentary. These items were given freely and frequently. Seen in this context, it is hardly implausible that Jackson would have gifted such an item to James during their close relationship.

The repeated attempts by Jackson’s defenders to discredit this specific anecdote speak to a broader tactic often used to delegitimise abuse survivors. Rather than engaging with the substance of James’s overall account, detractors focus on minor factual ambiguities or omissions as a way of calling everything into question. But as the civil complaint makes clear, James never denied having returned the jacket—he simply didn’t have the time or platform to explain that part within the constraints of a feature-length documentary.

In summary, James Safechuck did in fact receive one of the Thriller jackets as a child. He later returned it at Jackson’s request, a detail confirmed in official court documents. While critics have clung to this anecdote as evidence of dishonesty, the full picture reveals nothing of the sort. Instead, it highlights how easily public narratives can be distorted when key facts are ignored, either wilfully or through poor research. As is so often the case in these discussions, what is missing is not the truth, but the willingness to look for it.

With permission, the following article was translated and enhanced from The Truth about Michael Jackson.